Today’s political controversy over the education of Texas’ children is as intricate and contentious as it has been since 1845. With the myriads of news and media outlets, we are routinely challenged with sorting out the facts from opinions. But to make sense of the arguments and tasks at hand, we can only infer by conducting a deep dive to examine the historically significant developments from the past to the present. Indeed, we often lose sight of the importance of a historical perspective when we try to figure out the endless reverberations of political discourse without a comparative reference point. Our democratic standards as a nation are constantly shifting, probing our inner instincts to understand the invisible ramifications of critical happenings in real time. History provides us with a framework of different perspectives and interpretations that are essential in understanding today’s complicated political debates.

Recently, Texas legislators are poised to decide, yet again, on the fate of public education. A few years ago, political leaders touted public education as one of the most enduring and fundamental educational institutions in Texas. Indeed, public education was one of a few institutions that had the equal support of most Texans. However, today, the debate over how to fund state education is divided between those that support public education and those that support a voucher system to fund private schools. The latter position would reduce the amount of funds that are generally partitioned for public education. The voucher system is necessary, the proponents argue, because the public schools are not adequately serving their needs. It’s incumbent upon us to know and understand the historical nature of our public education institutions so we may have well-informed opinions on this matter.

In this article, I highlight key events that merge the past with the present to comprehend the issues, problems, and thus, offer new and innovative possibilities that can truly make a difference. I analyze racial conflicts, court cases and other impactful events that have contributed to the current system of the state’s public education. My focus is on how children of color experienced school in the face of extreme negative social conditions in an era that was greatly impacted by the economic crisis of the state and country. During a most stressful period of early development of Texas as a State, some of the major policies and laws promulgated were not in the best interest of these children. The newly formed populous couldn’t be more starkly different from one another, but they all held a common vision created from the promise of a prosperous future. Opportunities to prosper were afforded, then, and now, to mostly the White, Anglo-Saxon groups, but were systematically diminished for the Hispanic and Black communities. The most directly affected were the children whom nonetheless persevered. They are the unsung heroes of our past whose notable courage and perseverance cannot be overlooked.

Background Information: Public Education in Texas

To begin to put this discourse into context, I developed a table, attached at the end of this article (best supported on desktop computers): (Table 1 The Chronology of Significant Events Related to the Education of Latino Students in Texas). This table includes a few notes of importance that relate to Texas history, the Civil War, and the Reconstruction Amendments of 1868 – all of which bear relevance to the establishments of the state’s educational institutions. The Fourteenth Amendment is particularly important in the related research as it played a major role in the outcomes of multiple court cases. The Fourteenth Amendment includes the following statements:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

The Article VII, Section 7 of the 1876 U.S. Constitution is well-known for its provision to create separate schools for “the white and colored children, and impartial provision should be made for both.” This was at the core of the “separate but equal doctrine” that was used to justify racial segregation, although it should be noted that the ‘impartial provision” was disregarded, perhaps because this was not the intended goal.

The South and the Southwest U.S. were greatly impacted by the Plessy vs. Ferguson court case of 1896. The Jim Crow laws were used to racially discriminate against both Texas Hispanics and African Americans and in similar ways. Many of us recall this happening in our hometowns as recent as the 1960s. The Isis movie theatre in my hometown of Fort Worth, for example, required Hispanics and Blacks to enter the theater using a side door to the balcony since we weren’t allowed on the main floor.

During and after the Civil War, a period of intense reconstruction was evident, and in Texas, the agricultural economy was at its initial peak stages. Many White Texans that had migrated from the South readily transferred their racial, prejudicial views of African American laborers to the Mexican workers, and the newcomers from the Midwest had similar derogatory perceptions toward the Mexicans, akin to how they felt toward the of Native Americans.

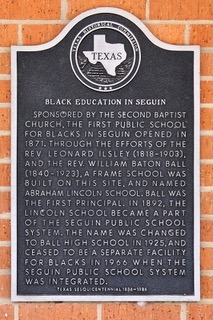

(1986) Sponsored by the Second Baptist Church, the first public school for blacks in Seguin opened in 1871. Through the efforts of the Rev. Leonard Ilsley (1818-1903), and the Rev. William Baton Ball (1840-1923), a frame school was built on this site, and named Abraham Lincoln School. Ball was the first principal. In 1892, the Lincoln School became a part of the Seguin Public School System. The name was changed to Ball High School in 1925, and ceased to be separate facility for blacks in 1966 when the Seguin Public School System was integrated. Click here for more information.

The farm settlers were dependent on slavery until it became completely prohibited by law. Then, they turned their attention to Mexican laborers that they could hire for very low wages. There was a strong resistance against educating the worker’s children since this was counterproductive to their business, and the children were not allowed to commingle with each other.

By the time the first “Mexican school” was opened in 1903 in Seguin, Texas, the Jim Crow law based on the “separate but equal doctrine” had taken root.

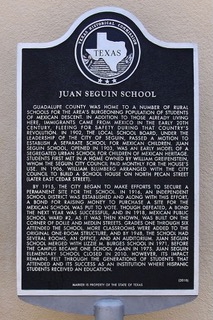

Guadalupe County was home to a number of rural schools for the area’s burgeoning population of students of Mexican descent. In addition to those already living here, immigrants came from Mexico in the early 20th century, fleeing for safety during that country’s revolution. In 1902, the local school board, under the leadership of the city of Seguin, passed a motion to establish a separate school for Mexican children. Juan Seguin School, opened in 1903, was an early model of a segregated urban school for children of Mexican heritage. Students first met in a home owned by William Greifenstein, whom the Seguin City Council paid monthly for the house’s use. In 1906, William Blumberg arranged with the city council to build a school house on North Pecan Street (later East Cedar Street). Click here for more information.

Historians point out that at least 18 school districts in South Texas had segregated schools in the 1920s. These were: Lower Valley/Valley: Edinburg, Harlingen, San Benito; McAllen, Mercedes, Mission, PSJA; Gulf Coast: Raymondville, Kingsville, Robstown, Kenedy, Taft; Winter Garden: Crystal City, Carrizo Springs, Palm, Valley Wells, Asherton, Frio City. Many other similarly segregated schools existed but were not officially documented. Between 1942 and 43, segregated schools were functional in 122 Texas school districts in 59 counties. Other states such as California and New Mexico in the Southwest documented similar patterns of racially segregated schools in racially segregated communities as well as throughout public establishments.

This was the segregated school era that characterized education throughout Texas, New Mexico, and California. Scholars in California like David G. Garcia, noted that in the 1920’s 80% of school systems across the Southwest United States experienced a segregated order. Other credible historical data indicate that 90% of schools in South Texas alone were segregated.

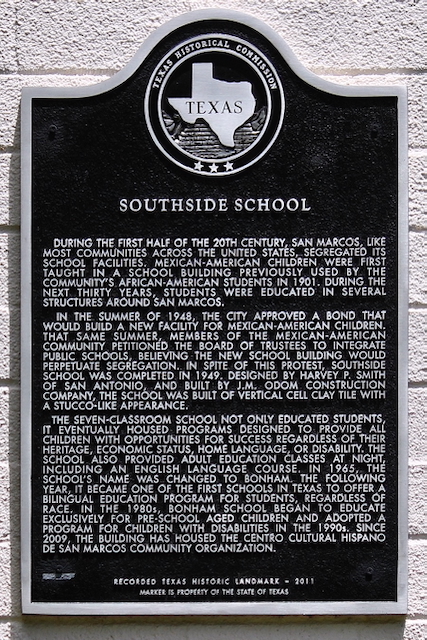

During the first half of the 20th century, San Marcos, like most communities across the United States, segregated its school facilities. Mexican-American children were first taught in a school building previously used by the community’s African-American students in 1901. During the next thirty years, students were educated in several structures around San Marcos.

In the summer of 1948, the city approved a bond that would build a new facility for Mexican-American children. That same summer, members of the Mexican-American community petitioned the board of trustees to integrate public schools, believing the new school building would perpetuate segregation. In spite of this protest, Southside School was completed in 1949. Designed by Harvey P. Smith of San Antonio, and built by J.M. Odom construction company, the school was built of vertical cell clay tile with a stucco-like appearance. For more information click here.

Segregation, in and of itself, served as an educational experience. Strong, intense negative perceptions directed toward a group of people unveiled the harsh reality that is well-recognized today as racism, and Mexican students were at the center of the crossfire. The following remarks are based on the research data collected by scholars and historians:

- Insults and disparaging remarks. School authorities, including administrators, school board members, and teachers were quoted the following in their efforts to explain why segregation was essential: the Mexican children had “mental retardation, language problems, poor hygiene, failure to appreciate education, and possessed an inherent inferiority.” (Montejano, p. 192)

- Racial Inferiority: White children were taught by their family members that Mexicans were “impure and to be kept in their place.” (p. 230)

- The “White” view that Mexicans should recognize their own inferiority and to accept segregation as a means by which to maintain order. (p. 230)

- Children understood that segregation meant that White children were superior, and Mexicans were inferior. The power was controlled by the White authority, ensuring their superiority status, and the inequality inherent in social reproduction. (p. 230)

- The class of farmers and growers who opposed educating Mexican children believed that education, including learning English, would steer them away from labor. They needed a class of people that would accept such difficult jobs at very meager wages. (p. 192)

- The “Mexican” schools were substandard, physically inferior. The children used textbooks and materials discarded by the White children. School Boards regularly provided the overwhelming share of the funds to the White schools. (p. 192)

A summary of life in a segregated school is described succinctly by the author David G. Garcia’s vivid account of what he terms mundane racism in his study of a California school district:

… the systematic subordination of Mexicans enacted as a commonplace, ordinary way of conducting business within and beyond schools. I utilize the term “mundane racism” to more precisely account for the way racism took place in Oxnard, and to understand the system of prejudice and discrimination against Mexicans designed to reproduce inequality as a routine matter of course. (p. 5)

Court Cases Before 1954

One of the earliest court cases in Texas that addressed the inequality of racial segregation was the Del Rio vs. Salvatierra case of 1930. Mr. Salvatierra was a concerned parent whose children attended a segregated “Mexican” school that had systematically been neglected in favor of the schools attended by White students. The court argued that a blatant inequality existed, while the defendants denied racial segregation in their schools, claiming that the Mexican students were “White” and not African American. Indeed, this was a weak argument and did not justify the existence of inferior schooling for Mexican students. However, the case was appealed, and a rehearing was denied.

Other similar court cases brought forth by plaintiffs demanding a halt to racial segregation were also quasi successful. In the cases filed against school districts in 1947, Hernandez vs. Driscoll and Delgado vs. Bastrop, the courts argued favorably for the plaintiffs. However, because of the school districts’ continuous challenges to the rulings, the outcomes were shortchanged.

In California, the 1947 Mendez vs. Westminster court case was particularly successful for a couple of reasons. First, the plaintiffs won on appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court that ruled against segregation, declaring it as unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. Secondly, the court case preceded the landmark federal case of Brown vs. Board of Education in 1954 in which similar arguments were used, and specific legal team members such as Thurgood Marshall, who later became a Supreme Court Justice, had participated in the case’s preparation.

Court Cases After 1954

The Brown vs. Board of Education of 1954 ruling had a significant effect on eliminating segregation in public schools. The court declared that the separate but equal doctrine was unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 added a crucial argument to court cases that sought a defense mechanism against practices of discrimination in schools and beyond.

At the federal level, the 1968 Bilingual Education Act provided specific funding for English Language Learners. In the 1981 court case of United States vs. State of Texas, the court ruled that the state educational agency “had failed to help ELLs overcome language barriers under the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA).” In response, the agency expanded the bilingual education programs to grades K-6 and ESL programs to include middle and high school students.

Although not entirely successful, the court cases have been instrumental in the efforts to improve the quality of education for all children, specifically for the most vulnerable students (the students of color, students with disabilities, etc.). In almost every professional segment of a society there exists a growing consensus that racial segregation, in its widespread and deeply embedded scale, was a malicious hindrance, thwarting well-intended educational improvement efforts in Texas and elsewhere. Indeed, in a comparative perspective, while Texans were entangled in the inferior realms of racial segregation, during the same period and in other parts of the world there were: Einstein who invented the theory of relativity, the great medical and science advancements, the empirical designs in math and physics, etc. Many would agree that the lesson learned, albeit as antiquated and uncomplicated as it may appear, is that the quantity and quality of our accomplishments depend on how much we’re willing to harness our capabilities and resources and focus our work on solving relevant problems or issues that affect all of us.

Symbolic Violence Replaces Hard Violence

In today’s modern society, many would argue that most of the blatant discriminatory practices of the past are non-existent, at least on a wider scale. Still and all, children are unjustly treated in schools because of their racial and/or language identity. As I point out in the article Blaming the Children, many important state agency’s policies that guide curriculum programs and practices as well as evaluation procedures are implemented with serious negative consequences. Additionally, there is a paucity of mechanisms to properly monitor programs and policies, thus, ensuring their utmost effectiveness. I also discuss the option of school reform efforts that can address the achievement gaps and overall improve the educational programs for these students. See Becoming Bilingual article.

A re-adjustment of our understandings of the past events is necessary to improve our capabilities as change agents. We agree that among the most significant social factors poverty and its devastating consequences were major causal factors. Indeed, we can identify Oscar Lewis’ explanation of his notions of the culture of poverty, which he introduced in the 1950s and 60s, when we examine the inflammatory inferior remarks aimed at the students, many of whom lived in extreme poverty conditions affecting their health and welfare. However, the culture of poverty explanation focuses on superficial or surface-level behaviors, obfuscating the real inferior social conditions that existed. Due to the work of scholars in the fields of the social sciences and education, an efficacious framework was developed, and its usefulness is currently applicable to expand upon this understanding, which I discuss in the following paragraphs.

The French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002), was one of the key contributors to the concept of symbolic violence. A type of non-physical violence, symbolic violence aims to engage others in the reinforcement of the status quo. Rather than resorting to physical, brute violence to compel compliance from subordinated individuals to the rules of domination, in symbolic violence the perpetrators, who hold and enforce their power, employ alternative means that are nuanced and subtle. In effect, the non-physical violence is an unconscious reinforcement of dominance whereby the subordinates are unaware of the actions perpetrated against them since they are presumably following the established rules or laws. Essentially, the dominant social group promotes self-aggrandizing norms to legitimize their authority and further suppress lower classes, thereby reducing opportunities of social equality.

Bourdieu and the insights of other key contributors introduced a novel and intriguing approach to scholarship in the social sciences. Their research provided deep insights into how power and dominance in social relations impact our democratic ideals and the rule of law.

Concluding Remarks

Researchers relied on analytical tools to critique the acts of symbolic violence that were perpetrated against the Mexican and African American students, such as racial segregation and racial bullying. To endure the constant and systematic threats against them, these students had to learn to fend for themselves and become self-reliant and resilient. Their acts of courage are a testimony of their tenacity and strength in the belief that as Texans they have the same rights as others to obtain access to a quality, equitable education. Their impactful memory serves as a reminder of our work as educators and stakeholders, and the need to continue in securing the optimal opportunities for educational and social equality.

Please visit this article and others in the Bilingual Fronteras website.

Research Notes

Please note that the word Mexican is used interchangeably with Hispanic and Latino, and that in the instance where I use Mexican or Mexican American it is for the reason to remain constant with the pertinent resource(s). I use the term “White” to refer to individuals with Anglo-Saxon heritage. This term is used in the research literature.

Book sources:

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge, 1984.

- Lewis, Oscar. (1961). The Children of Sánchez: Autobiography of a Mexican Family. Random House, Inc. (Film, 1979)

- Montejano, D. (1987). Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836 – 1986. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Taylor, P. S. (1934). An American-Mexican frontier: Nueces county Texas. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina.

Article:

- García, D. G. (2018). “Strategies of segregation: Race, residence, and the struggle for educational equality.” Berkeley: University of California Press.

Internet Sources:

- School Choice, vouchers and the future of Texas education

- Historical Marker Database

- Texas State Historical Association

- Texas Historical Commission – Texas Historic Sites Atlas

Table 1 Chronology of Significant Events Related to the Education of Hispanic Students in Texas

1836 1845 1846 -1848 1861 -1865 | Significant Historical Notes: Texas declared its independence from Mexico. Texas annexed as the 28th state of the Union. Invasion of Mexico by the US army. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo signed in 1848. Civil War – Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation |

| 1868 – Reconstruction Amendments | 13th Amendment: Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude … 14th Amendment: All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. 15th Amendment: The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. |

| 1876 | Article VII, Section 7, of the Constitution of 1876: Separate schools shall be provided for the white and colored children, and impartial provision shall be made for both. |

| 1896 | Legal and Policy Cases: Plessy vs. Ferguson: the Court sustained the constitutionality of Louisiana’s Jim Crow law. |

| 1902 | De facto segregation fact: First “Mexican” school built in Seguin, TX. |

| 1920s | Segregated Schools: Lower Valley/Valley: Edinburg, Harlingen, San Benito; McAllen, Mercedes, Mission, PSJA; Gulf Coast: Raymondville, Kingsville, Robstown, Kenedy, Taft; Winter Garden: Crystal City, Carrizo Springs, Palm, Valley Wells, Asherton, Frio City; many others not officially documented. |

| 1942 -1943 | De facto segregation: Segregated schools were functional in 122 districts in 59 counties in Texas. According to various historical data sources, 80% to 90% of school systems throughout the Southwest United States sustained segregated schools. |

| 1930 | Del Rio vs. Salvatierra – Jesus Salvatierra, parent, Mexican students deprived of the benefits afforded “other White races,”On May 15, 1930 District Judge Joseph Jones heard the case, ruled in Salvatierra’s favor, and granted an injunction. Texas court of appeals ruled the injunction was voided and rehearing was denied. (1971) |

| 1947 | Mendez vs. Westminster – This case challenged the segregation of Mexican American students in California schools. Mexican Americans were often labeled as “white” in official census categories yet were segregated into separate and unequal schools. Plaintiffs provided evidence that school districts explicitly created segregation. Judge McCormick ruled in favor of plaintiffs. The school districts appealed claiming that the federal courts did not have jurisdiction over education. However, the Ninth Circuit ruled that such segregation was unconstitutional under the 14th Amendment. (Seven years later, 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education) |

| 1948 | Hernandez vs. Driscoll – The court found the Driscoll grouping of separate classes arbitrary and unreasonable, as it was directed against all children of Mexican origin as a class, and ordered the practice halted. Although the decision prohibited segregation of Mexican-American students in public schools, however, the system did not change radically, and in fact subsequent challenges became necessary. Delgado vs. Bastrop ISD – The court ruled that maintaining separate schools for Mexican descent children violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. Nevertheless, failure to enforce this ruling resulted in continued legal challenges through the 1950s and 1960s; arguments first presented in the Salvatierra case were heard as late as 1971 in Cisneros v. Corpus Christi ISD. |

| 1954 | Brown vs. Board of Education. This landmark Supreme Court case struck down racial segregation in public schools (“separate but equal doctrine”) as unconstitutional under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. |

| 1964 | Civil Rights Act – prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Provisions of this civil rights act forbade discrimination on the basis of sex, as well as, race in hiring, promoting, and firing. The Act prohibited discrimination in public accommodations and federally funded programs. It also strengthened the enforcement of voting rights and the desegregation of schools. |

| 1968, 1975 | Cisneros vs. Corpus Christi ISD – Judge Woodrow Seals found in 1975 that the school board consciously fostered a system that perpetuated traditional segregation. Judge Seals cited the “other White” argument as adjacent proof of segregation, but relied primarily on the application of unconstitutional segregation of Mexican Americans as an identifiable minority group based on physical, cultural, religious, and linguistic distinctions. |

| 1968 | The Bilingual Education Act, Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1968: Establishes federal policy for bilingual education for “economically disadvantaged language minority students” that allocates funds for innovative programs, and recognizes the unique educational disadvantages faced by non-English speaking students. |

| 1971 | United States vs. State of Texas – The federal court ordered the San Felipe Del Rio CISD to desegregate and provide equal educational opportunities to all students – based on 14th amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. As a result of the lawsuit, the federal court came down with a court order, Civil Action 5281, which eliminates discrimination on grounds of race, color, or national origin in Texas public and charter schools. |

| 1973 | Keyes vs. School District No.1 – This federal Supreme Court case examined de facto/de jure segregation in Denver, Colorado, where no explicit laws enforced school segregation. Instead, plaintiffs argued that school district policies (gerrymandering attendance zones, school siting, etc.) had the intent and effect of racially segregating schools. (Similar to Cisneros vs. Corpus Christi 1971.) It is one of the first major Supreme Court cases to include Latino plaintiffs and concerns about their treatment under segregation. |

| 1974 | Lau vs. Nichols – Supreme Court case that ruled that schools must provide language instruction to students with limited English proficiency. The court’s decision established that this lack of instruction violated the Civil Rights Act of 1964. |

| 1974 | Serna vs. Portales (NM) – This was the first case to raise the issue of bilingual education outside of the context of desegregation. It was argued under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of “race, color, or national origin” in any program that receives federal funding. The court found the school’s program for these students to be inadequate. Upon appeal, the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals decided in favor of the plaintiffs in 1974, just six months after Lau. |

| 1981 | United States v State of Texas (Texas Education Agency) – the District Court found that the State had failed to help ELLs overcome language barriers under the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA). While the case was on appeal, Texas passed a law expanding bilingual education to grades K-6 and providing for English as a Second Language (ESL) programs for middle and high schools. |

| 1981 | Castañeda vs. Pickard – The case originated in Texas, where plaintiffs charged that the Raymondville Independent School District was failing to address the needs of ELL students as mandated by the EEOA. The federal court ignored the old assumption that Lau and the EEOA mandated bilingual education. A major outcome of this case is a three-pronged test to determine whether schools are taking “appropriate action” to address the needs of ELLs as required by the EEOA. |

| 1981 | Plyler vs. Doe – Under the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the state does not have the right to deny a free public education to undocumented immigrant children. |

| 1984, 1995 | Edgewood ISD vs. Kirby – The Edgewood lawsuit occurred after almost a decade of legal inertia on public school finance following the Rodríguez v. San Antonio ISD case of 1971, which asked the courts to address unfairness in public school aid. Rodríguez plaintiffs ultimately lost in the United States Supreme Court in 1973. |

| 1836 1837 1845 1846 -1848 | Historical Notes of Texas, U.S., & México: 1810 – 1821 Mexico gains independence from Spain after 300 years of Spanish colonial rule. Texas declares independence from Mexico, known as the Republic of Texas. The declaration signed during the Texas Revolution which began in October 1835. The United States government recognizes Texas’ independence. Texas was annexed by the United States as the 28th state of the Union Invasion of Mexico by the US army. Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, 1848. U.S. paid México $15 million for territory. |

Please visit this article and others on Bilingual Fronteras website.