According to the April, 2017 article, “Central American Immigrants in the United States by Gabriel Lesser and Jeanne Batalova,” in 2015, eight percent of the 43.3 million US immigrants lived in the U.S., and the majority (85 percent) were from the three of the seven Central American countries. Immigrants from the three countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, known as the Northern Triangle, made up the largest growth in U.S. population since 1980 (90 percent).

The following chart displays the population of Central Americans in the United States according to country as of 2015. (credit: Migration Policy Institute, April 5, 2017)

| Region/Country |

Number |

Percent |

| Central American Total |

3,385,000 |

100.0 |

| El Salvador |

1,352,000 |

40.0 |

| Guatemala |

928,000 |

27.4 |

| Honduras |

599,000 |

17.7 |

| Nicaragua |

256,000 |

7.6 |

| Panama |

104,000 |

3.1 |

| Costa Rica |

90,000 |

2.7 |

| Belize |

49,000 |

1.4 |

| Other Central American |

7,000 |

0.2 |

According to the authors of the report (Lesser and Batalova), the Central Americans who have acquired “legal residency” also known as “green card,” have done so via family reunification channels, i.e., the process of the immigrant request and granted location of residence in the U.S. with a family member who resides in the U.S., that may or may not have the legal residence status.

Another way of migrating to the U.S. is through the Temporary Protected Status (see article by Madeline Messick and Claire Bergeron, July 2, 2014) or TPS, which nationals from El Salvador and Honduras have been beneficiaries. The TPS is granted by the U.S. government and allows individuals from designated countries to seek protection from deportation and to work, although it doesn’t include a “green card.” In fact, the specific provisions of this temporary status are that the beneficiaries are not eligible to receive permanent residency nor citizenship. Once, the TPS expires, if the U.S. does not renew it, the beneficiaries’ immigration status is back to the very beginning. At the time the article was written in 2015, there were 212,000 Salvadorans and 64,000 Hondurans that were in the U.S. with a TPS. The U.S. grants TPS designations to six countries besides El Salvador and Honduras: Haiti, Nicaragua, Syria, Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan. A total of 340,310 reside in the U.S. with protection from the TPS (Guatemala is notably not on the list.)

Countries may be designated TPS based on one of three reasons: there is an ongoing, armed conflict that poses great danger if the migrant returns; as a result of a disaster such as an earthquake, flood, health epidemic, etc., a country may request a TPS designation until it is safe for its people to return; and, “extraordinary and temporary” conditions that prevent the people from returning safely.

Unauthorized Immigration

According to Rosenblum and Soto (2015: see report, “An Analysis of Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States”) there are 436,000 Salvadorans residing in the United States. An additional 212,000 Salvadoran have been granted Temporary Protected Status. A great number of Salvadorans live in California and Texas, but also, in the East Coast: Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C.

Approximately 704,000 Guatemalans live as “unauthorized” in 38 states and the District of Columbia. In California alone, there are 200,000 Guatemalans. However, Guatemalans are also dispersed throughout 12 states in the East Coast, and around 10,000 reside in the states of Tennessee, Illinois, and Alabama.

About 317,000 Hondurans live as unauthorized immigrants in “significant numbers” in 23 states, but they are concentrated in Texas and Florida. They also reside in California, the East Coast and Louisiana. The number excludes the 64,000 Hondurans that reside with a Temporary Protected Status.

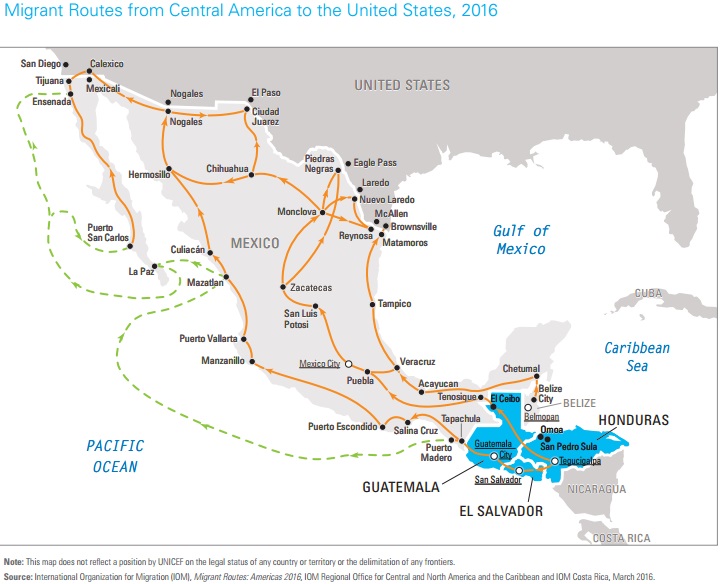

U.S. Money to Stop the Migration

As a result of the surge of Central American unaccompanied children in the 2014, the U.S. State Department allocated 86 million dollars for Mexican authorities to “stop” the flow of migrants to the U.S. border. Although, Mexican laws address special protection measures, the implementation of these policies are uneven and flawed (see article, “Strengthening Mexico’s Protection of Central American Unaccompanied Minors in Transit”). Amongst the essential gaps in the implementation were “poor screening and inadequate housing,” and in 2016, less than 1 percent of the 17,500 unaccompanied children which were stopped by Mexican authorities applied for asylum, but no assurances were given that their requests would be granted. Critics noted that in most cases, children were not asked if they wanted to seek asylum in Mexico. Another serious angst among critics was that so many unaccompanied youth detained and deported would be returned to a very dangerous situation in their country. The women’s stories strongly suggest that there are substantial situations to warrant these fears and concerns.

According to an interview with National Public Radio (NPR), writer Sonia Nazario explains that the “catch and deport before they reach the border” has not deterred the Central American migration, and in fact, made the journey more dangerous. The migrants were kept from riding on top of the train that winds its way toward the north (called “la bestia or the beast”), thus, their journey through the Mexican routes became more perilous, and “open season on migrants,” by locals such as cartel or gang members, and even enforcement authorities. One of the women’s stories in this collection includes such a kidnapping and extortion incident (see “Jenni’s Story”). Additionally, the shelters, once a restive place for the weary migrant, are becoming like refugee camps where migrants must deal with the Mexican barrier that they must navigate and overcome.

The Case of the United States Funding Honduras

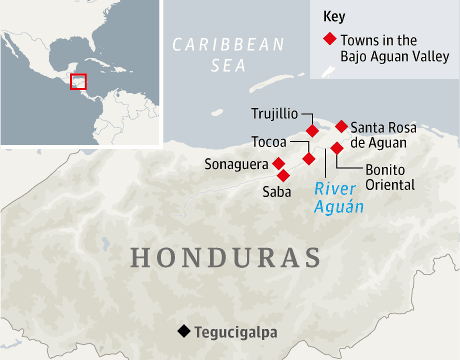

The collection, “In the Shadow of the Half Moon” includes, in each story, a breakdown on how the problem of police corruption played a major factor in the women’s tragic circumstances. The women were not able to seek protection from the police and other authorities, and to a lesser extent, justice for crimes committed against them. In the case of Honduras, not only are police and the military complicit in crimes described as human rights abuses, as well as murder, but in a twist of cruel injustice, and despite the track record of human rights abuses, the Honduran government receives aide from the United States in the form of $18 million plus a $60 million loan from the Inter-American development Bank, approved by United States (see article, “America’s Funding of Honduran Security Forces Puts Blood on Our Hands”). Critics of the aid consistently allude to the abuses of military police forces that have resulted in nine killings, 20 cases of torture, 30 illegal arrests between 2012 and 2014, and 24 soldiers are under investigation for the killings (see Human Rights Watch Report). Also, and very disconcerting, over a 100 activist whose farm lands were at risk of becoming exploited for corporate greed have been killed since 2009. The Honduran security forces are suspected of the murders but the lack of substantial results have unnerved Hondurans and lost their confidence in the justice system. Honduran President Hernández’ use of military might for domestic purposes is clearly in violation of the country’s constitution and many critics urge the United States to withhold funding until the human rights abuses have been resolved.

Reasons Why They Migrate Run Deep and Broad

Why do thousands make the decision to migrate to the United States, legally or illegally, risking their lives and forging a new life strife with unknowns and incredibly stressful? Understanding the reasons requires more than just a cursory knowledge of each country’s history, especially on how events shaped the aspects of social, infrastructure, economic, and political situations. Many writers and journalists offer critiques on the current affairs of the three countries by pointing to the United States past role or intervention such as in the civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. Valeria Luiselli is one such writer, adding that gang violence in the Northern Triangle region is largely due to the deportation of gang members from cities in the United States to the region in the 1980’s. However, Luiselli is most critical of Obama’s administration immigration policies during the 2014 peak migration of Central American unaccompanied youth. The juvenile cases were ordered to be processed as quickly as possible within a three-week window (see her article, “Why did you come to the United States?” Central American Children Try to Convince Courts They Need Protection”). The “fast track” system didn’t allow the youth to develop defense against deportation, so the odds against them were stacked, especially without a legal counsel to represent them. To Luiselli, the government acted in the most cruel and irresponsible manner, leaving the asylum seekers with no other choice but to be deported to the dangerous places they tried to escape. As long as the United States government refuses to acknowledge their role in causing the roots of the problem, and by refusing to describe the children as “refugees,” the migrant children will not be treated fairly and justly.

Journalist Julia Preston writes about the legal problems of Central American parents and their children in the United States courts. She notes that out of the 100,000 cases that have addressed the immigration courts since 2014, only 32, 500 cases have been issued rulings, and a staggering 70 percent of those cases concluded with deportation orders “in absentia,” whereby the migrants did not show up for the hearing and yet received deportation orders. The immigration courts are problematic for many reasons, and needless to say, the migrant cases are clearly marked for deportation and an otherwise ruling would have to be based on the judges’ notions for the migrants seeking asylum. See article, “Fearful of Courts Asylum seekers are banished in absentia.”

The Northern Triangle Countries

El Salvador

El Salvador’s historical accounts of war and violence includes the uprising or revolt of the 1930’s that culminated with a battle that resulted in the massacre of 30,000 indigenous peasants on the side of land reforms, and to end the wide inequality wrought by centuries of the dominance of the oligarchy (the “fourteen families”). The uprising was led by members of the so-called communist party, which was generated by Farabundo Martí and others, although Martí’s name remains as a central symbol in the political party, the Farabundo Marti Liberation Front, or as it was named in 1980, the FMLN. After the slaughter of innocent people known as “La Matanza” in 1932, Marti was executed by the same dictator, President Hernández Martínez, that ordered the killings of the indigenous peasant/farmers. (See article, “El Salvador 12 Years of Civil War,” the Center for Justice and Accountability’s Transitional Justice Project.)

Although the massacre highlighted the ending of a chapter in El Salvador’s history of war, the conflict continued. Throughout the 60’s and 70’s, right-wing paramilitary death squads and left-wing guerillas fought each other continuously, and in 1979, in an attempted coup, the dictator Carlos Romero, was ousted by “moderate” leaning officers, and a new government, the Revolutionary Government Junta, or the JRG was formed. But, in the following year, the JRG leaders resigned after an intense battle with the right-wing faction that used violent tactics to win their cause, such as bombings, kidnappings, and murder. Behind the ousting of the JRG as well as the murder of Archbishop and human rights defender, Oscar Romero, was a Salvadoran Army officer Roberto D’Aubuisson. He was briefly jailed but was freed due to the violent pressure imposed by his right-wing comrades. D’Aubuisson was a major force in the formation of the right-wing political party, the Nationalist Republican Alliance Party or, ARENA, and remained a leader of the death squads throughout the Civil War of 1980-1992.

The FMLN emerged as a military/guerilla organization after four other similar groups were integrated. After the FMLN attacked the government with all its force, the United States began to support the right-wing government with military aid and advisors. The US intervention has long been criticized for its role in supporting a government that was not formed via democratic means. The US ambassador during this time, Robert White, was very critical of the “atrocities” committed during the counter-insurgency, and even referred to D’Aubuisson as a “pathological killer.” But, the Reagan administration was adamant about supporting the government, and even removed Ambassador White.

Salvadorans experienced the extreme horrors of war, and the infliction upon its people was unbearable. Besides the assassination of Archbishop Romero, beloved and respected by the largely Catholic community, there was also the despicable and horrendous crime of rape and murder of four American churchwomen by military and paramilitary forces in December of 1980. Then US president, Jimmy Carter, cut off aid to El Salvador, but was deftly restored with the election of President Reagan in 1980. To end the insurgency, the US provided the Salvadoran government with substantial military support, which led to the formation of the “Rapid Deployment Infantry Battalions,” a military arm trained by the US to carry out unspeakable war crimes. One such atrocity was led by the brigade, the Atlacatl, when, in the Fall of 1989 they descended upon the University of Central America and murdered six prominent Jesuit priest, their housekeeper and her daughter. The Atlacatl was the same brigade that had led the now infamous El Mozote Massacre in 1981. In December of 1981, an entire village, El Mozote, was annihilated within three days, using a scorched-earth tactic by the Atlacatl Battalion, armed and trained by the United States. Reports indicate that up to 1,000 civilians, men, women and children were murdered, while many were tortured before their executions. The known lone survivor, Rufina Amaya, was able to give testimony to the horror she experienced, including the killings of her family.

The 12-year Civil War that engaged the government and the guerilla and paramilitary forces resulted in the deaths of 75,000 Salvadorans due to massacres, executions, landmines, and indiscriminate bombing. The human rights violations were extreme where civilians were tortured, mutilated, disappeared forcefully, murdered, and women were raped. And although the left-wing political party affiliates blame the “amnesty law” that was shaped by both the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), in reality no one paid for the injustices. Thus, Salvadorans live with a void in their lives, having experienced the horrors of war as victims or survivors and knowing that the people responsible would never be charged, much less punished. (See “The Salvadoran Town that Can’t Forget” by Sarah Esther Maslin.)

Street Gangs of El Salvador

Perhaps, the most pressing problem in El Salvador is the organized gang, criminal activity that has permeated throughout Salvadoran society. The presence, indeed, the integration of gangs, notably MS-13 and Calle 18, have transformed the lives of so many, however, to many people that lived through the Civil War (1980-1992), the conflict between the two warring gangs and the military police and death squads is far worse than the Civil War (see “What We Have Now is a War,” by Maslin, Ramos, & Martinez, 2016) . According to the interviewees in the excellent documentary, “Gangs of El Salvador,” (published by Vice News on November, 2015; featuring correspondent Danny Gold) the Civil War is still on-going, but in comparison, the three-way conflict has far more complications.

El Salvador’s murder rate is destined to surpass Honduras that had been described as the murder capital of the world. El Salvador had almost 6,000 murders in 2015, as noted in the documentary synopsis, the highest number since the end of the Civil War in the 90’s. In a country of six million, the number of murders is too phenomenal to grasp in understanding its significance. The number of gang members vary according to the source, but some have stated as many 60,000 gang members live in El Salvador. Thousands live in prisons. The gangs actually originated in Los Angeles, in the 1980’s, which many point to the Civil War as the cause of the migration, spurring the exodus of thousands into the region. (Recall the United States’ role in supporting the right-wing factions in the Civil War during that time.) But, in the ensuing years, thousands of gang members were deported and became integrated into the Salvadoran gang life. The documentary features interviews with a variety of Salvadorans: mothers of young victims, families of gang members, ex-paramilitary and relative of victims of gang violence, a Calle 18 gang leader, gang members inside prisons, and others that would not speak on camera for fear of retaliation. Their testimony coincides with the women’s stories featured in the collection, “In the Shadow of the Half Moon,” and underscores the extent of the conflict throughout El Salvador: the fear of parents losing their children to the gangs, as recruits or victims; the extortions that take food from the table of one hard working, law abiding family to another family engaged in gang violence; the political climate that misses the mark in understanding how to deal with such a huge, multi-faceted problem, where politicians opt for the familiar “mano dura” or heavy-handedness approach, putting away gang members to languish in dangerous prisons or deploying death squads to kill them. The military force and the gangs accuse each other of being “terrorists.” Salvadorans see their country in ruins and worst, they believe that it can’t be re-constructed.

For more information on street gangs of El Salvador, go to “Migration From El Salvador to the United States Largely Due to Street Gang Violence and Related Factors,” in this blog.

Honduras

Honduras, a country of 9.1 million people, has the unfortunate distinction of being a country of violence, where one of its city, San Pedro Sula, is the most violent city in the world (or closely behind Caracas, Venezuela), with a rate of 173 homicides per 100,000 residents. Reportedly, in 2013, an average of 20 people was murdered every day. (See article, “Inside San Pedro Sula – the Most Violent City in the World,” by Sibylla Brodzinsky and published by the Guardian in 2013.) Honduras is also the third poorest country in the western hemisphere: 62.8% or 6 out of 10 households live in extreme poverty.

The re-election on March 2017 of Juan Orlando Hernández, a rightwing Nationalist, pro-business, pro-security manifesto was replete with allegations of electoral fraud and voter intimidation. Critics of the president and his party cite the extreme human rights violations by the United States supported military and the private security forces hired by the corporations or wealthy owners that overpower the peasants and farmers who seek to protect their traditional lands from mining and oil corporations, exploiting the properties and displacing the residents, as well as corrupting the environment and tearing apart the economic and social well-being of the communities. The economic inequalities are deeply embedded in Honduran society since it is a straightforward oligarchy controlled by 10 wealthy families. The term given to describe Honduras, the “banana republic” (coined by author O. Henry) aptly describes the wealth distribution of the wealthy versus the working class.

At the turn of the century, Honduras’ banana companies (the United Fruit Company) became a huge cash crop for the owners and investors. However, the companies receded and bananas were gradually complemented with a diverse array of fruits such as pineapple, grapefruit, and coconut. In the 1980s the fertile Aguan region was the fruit basket of Honduras that provided jobs and edible products for its people. However, the recent development of the African palm plantations has replaced the edible products, up to 50%. African palm is harvested for the saturated oil which is used for processing foods, and as biofuel. The African palm industry has caused economic instability among the poor, working class, but has served as a lucrative investment for the wealthy.

As discussed in the abovementioned section, “The Case of the United States Funding Honduras,” the US influence and presence are evident in the military and funding support, plus there are several US military bases in the country. Honduras is a major point of transit for cocaine; as much as 300 tons pass through Honduras from South America. But, community leaders have become increasingly vocal in their complaints about the military forces joining with police and security forces to combat the MUCA (Movimiento Unificado Campesino de Aguan) resistance by using their military might to violate human rights, including injuring and murdering innocent people, stealing lands belonging to the people, and raping women. Private security guards paid by the companies outnumber the police force: five guards for every police officer. A type of “police state” serves to further suppress the working-class people that are clearly powerless, economically and politically.

City life in Honduras has problems of its own. In 2000, the mayor (Roberto Silva) declared San Pedro Sula as a thriving center of industry, and commercial and financial development. The clothing maquillas were notably successful, and the city contributed two-thirds of the country’s GDP (gross domestic product). However, beset with one of the worst hurricanes in the country in 1998 (hurricane Mitch), and a military coup in 2009, unemployment increased exponentially, affecting everyone from the middle class to the most vulnerable social and economic groups.

San Pedro Sula, besides stricken with economic and social woes, has one of the worst gang or criminal organizations, perhaps, in all of Central America. The two dominant gangs, the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and Barrio 18, control three sectors of San Pedro Sula (see article, “A Snapshot of Honduras’ Most Powerful Street Gangs” by Kyra Gurney). Over a thousand gang members from each gang work the streets of their territories, both making up 60 percent of the total gangs in Hondarus (see article, “Interactivo: Evolución de las maras en Honduras” for information on the areas controlled by either gang). The women in this blog’s collection consistently describe the gang’s internal conflicts, killing each other indiscriminately and causing havoc among the neighborhood, and many times innocent bystanders become victims of their battles. But beside the battles, which seem to erupt spontaneously and run a course of unpredictable duration, the gangs focus on maintaining their territories, either by seizing control or ensuring that they remain in their possession (see article, “Appraising Violence in Honduras: How Much is Gang-Related?” by M. Lohmuller & S. Dudley). Gang members use their “territories” to claim their physical space such as specific neighborhoods, and their “right” to invoke their power over the people via extortion, kidnappings, and even murder. But, gang members also reserve their power to seize control (and notoriety) for personal purposes. Reports from some sources point out the observable differences between the gang organizations: the MS13 shoot people whereas the Barrio 18 gang members use torturous tactics and then, mutilate the bodies and publically display them for the effect they seek (see article, “Life and Death in the Most Violent Country on Earth” by Flora Drury). The majority of the murders are unsolved, especially when the killings are deemed the work of gangs. There are instances when some sort of “superficial” actions for seeking truth and justice are practiced by the police, judges, and politicians, but for the most part very little to nothing is done to protect the people or punish the guilty for their crimes. It is no wonder that gang members feel empowered to run rampant their terror and deadly assaults on others with impunity.

Due to the economic, repressive, and violent gang activities and other related realities that Hondurans live each day, their inclinations to leave are understandable, but for many the choice to leave or stay is not an option since their lives or those of their loved ones, are in grave danger.

Guatemala

“Guatemala,” a “place of trees” was the name told to the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado used to describe the country by Nahuatl-speaking, Tlacaltecan soldiers, whom were among the entourage that Hernán Cortes had given permission to conquer in 1519. Indeed, Guatemala is known for its natural beauty with its abundance of such unique ecosystems whose biodiversity is renown all over the world. But Guatemala has experienced so many misfortunates, and today, it is a country with very low poverty levels: half the population of 15.8 million lives below the poverty line and according to the United Nations, 17 percent are categorized as extremely poor. Additionally, Guatemala, the most populated Central American country, has the lowest literacy rate with 25 percent of individuals over the age of 15 listed as illiterate. Even though the majority of Guatemalans are fluent or semi-fluent in Spanish, among them are 42 percent mestizo, and approximately 41 percent are described as an indigenous people; they are speakers of one of the 21 Mayan languages, including K’iché; Kaqchikel, Mam; Q’eqchi’: or two non-Mayan languages: Garifuna or Xenca. The indigenous people suffer disproportionately due to the rampant racism at institutional and social levels, and women and children seem to be the most vulnerable victims. The woman’s story in the abovementioned collection highlights the problems often shared by other women in similar situations.

1950’s and Early 60’s

Guatemala’s history is replete with political and civil unrest. A few highlights are discussed here.

In 1957, General Miguel Ydgoras Fuentes assumed power, under alleged rigged elections, after the then President Carlos Castillo Armas was assassinated. Ydogoras who authorized the training of 5,000 anti-Castro Cubans in Guatemala, provided airstrips in the region of Peten (later became the US-sponsored failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961). But in 1963, Ydogoras was ousted in a coup led by Colonel Enrique Peralta Asudia. The junta of 1963 (which wanted Arévalo to return from exile) was forcefully stalled by a coup backed by the Kennedy administration and the New Regime dominated the terror against the guerrillas that had begun under Ydgoras.

In 1963, Julio César Méndez Montenegro was elected president of Guatemala and during his right-wing paramilitary, organizations were formed like the “White Hand” and the Anti-communist Secret Army, which were the forerunners of the “Death Squads” that caused havoc on civilians during the Civil War (1960-1996). Military advisors from the US Special Forces (Green Berets) were deployed to Guatemala to train troops in these organizations into an army, a modern counter-insurgency elite force, which became the most sophisticated killing machine in Central America.

1970’s, 80’s and 90’s

In the 1970’s, two new guerilla organizations, the Guerilla Army of the Poor (EGP) and the Organization of the People in Arms (ORPA) began attacks against the military and some civilian supporters of the army. The paramilitary forces responded with a counter-insurgency attack that resulted in tens of thousands of civilian deaths. Due to the widespread and systematic abuses against civilians, the US ordered a ban on the support for aide toward the government forces. It should be noted that although then President Carter was behind the ban, American aide continued albeit through undisclosed means.

On January, 1980, a group of K’iche’ activists attempted to take over the Spanish Embassy to protest the massacres in the indigenous areas of the country but were overcome by Guatemalan forces that resulted in the deaths of every K’iche’ activist and the embassy was burned to the ground. However, a lone survivor of the assault and ensuring fire laid claim to the fact that the Guatemalan military killed the intruders and set the embassy on fire to erase the killings, thus, disputing the testimony of the Guatemalan soldiers who had claimed that the activist had set themselves and the embassy on fire.

General Efrain Ríos Montt became president of the military junta in 1982, whom President Reagan described as “a man of great personal integrity.” Ríos Montt continued the warfare known as “scorched earth,” responsible for the genocidal massacres of thousands of indigenous people, especially the Ixil, which were targeted for supporting the “resistance.” He was later found guilty of crimes against humanity. The court proceedings were broadcasted internationally in the Spring of 2013, and many indigenous women testified to the atrocities perpetrated toward men, women, children, and even infants. The women were perceived as courageous for their fortitude to stand up against Ríos Montt and others responsible for the torture and killing of their families and other innocent people.

But the 36-year Civil War had far more consequences than initially concluded. Although the government military forces carried out 93 percent of the human rights violations, which constituted war crimes, the US government via the CIA was complicit in these crimes because they trained the paramilitaries. (See “Guatemala Memory of Silence” by the Commission for Historical Clarification.) Over 450 Mayan villages were destroyed, a million people were displaced and approximately 200,000 people died. Most of the victims (83 percent) were Maya. Whether the war crimes constituted genocide was addressed in several reports and the conclusion was clearly stated that indeed, the military government’s actions constituted genocide. Although Ríos Montt was held largely responsible for the crimes against humanity, and was found guilty, the verdict was nullified due to legal proceedings. A retrial had been scheduled but was later suspended (see “Genocide Trial for Guatemala Ex-dictator Rios Montt Suspended”).

The United States Involvement

The US involvement in Guatemala’s history can be described as interventionist. President Truman’s interests in Guatemala were political, which at the time even the appearance of a communist government in the Americas was perceived as a threat. But, it was also perceived as an investment since the United Fruit Company had experienced lucrative success. But Guatemala’s incoming president, Jacobo Arbenz, brought forth agrarian reform, granting uncultivated land to peasants, and infuriating investment holders of the United Fruit Company. In 1952, President Truman ordered an overthrow of Arbenz but was unsuccessful. Soon afterward, President Eisenhower was elected and took up the plan to oust Arbenz by ordering the CIA to arm and train 480 Guatemalan soldiers, and in 1954 carried out a military invasion in Guatemala. Even though the military created a psychological warfare instead, its deployment was successful because it led to Arbenz’s resignation.

In 1963, the Kennedy administration supported a military coup that derailed the election of Juan José Arévalo, a politician who had the vision of Franklin Roosevelt’s social agenda and had been in exile since 1950. At that time, a strong campaign of terror to kill off the guerrillas was accelerated. The Civil War began in 1966, during the presidency of Julio Méndez who allowed the CIA to broadly and freely carry out their military agenda with the Guatemalan government.

The Civil War ended in 1996 when a Peace Accord was brokered by the United Nations between the guerillas and the government.

The Development of Gangs in the 1980’s

In her 2013 book, Adiós Niño: The Gangs of Guatemala City and the Politics of Death (see Review), Deborah Levenson makes the connection between the historical events in Guatemala and the social, political, and economic realities that have impacted gang members in the urban settings. The displaced Maya peasants, fleeing their countryside communities settled in loosely planned neighborhoods that seemed to grow exponentially overnight. But, it followed a pattern within a 20-year time span, and thousands of weary peasants started their new lives in unknown areas. The ex-military and paramilitary men became unemployed and added to an already huge unemployment problem. Or, they became security guards in legitimate and illegitimate businesses. Free trade capitalistic systems denigrated the working-class echelons, and those that chose to fight via unions were defeated. Thus, Levenson concludes that the structures of MS-13 and MS-18 were borne from this kind of environment. Even the gang members with their empowered status and weapons feel powerless. See Homicides in Guatemala.