Most of us have a pretty good understanding of segregation and how it differs from integration. Among the most significant events in our history of public education is the landmark SCOTUS, 1954 decision of Brown v. Board of Education, filed under the plaintiff’s name, Linda Brown, an African American student in Topeka, Kansas. The case, brilliantly argued by Thurgood Marshall and others, puts to rest the 1874 “separate but equal legislation,” citing its unconstitutionality and transforming our country’s public education system. Nine years prior, in 1947, Mendez v. Westminster in California, the court ruled against the segregation of Mexican American students, advancing the cause against school segregation. However, these and other related cases did not totally disallow segregation in neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces, that according to social scientists, have far-fetched consequences that most Americans are unaware. In a recent article, sociologists Miljs and Usmani,* used an innovative computational simulation model to predict that the present-day social worlds will become increasingly segregated, exacerbating the divisions amongst people, and creating a greater inequality equilibrium. In this post I discuss the implications drawn by the authors, and how these are relevant in our efforts toward improvement, especially in schools and other key democratic institutions.

Some of you may recall the adage, “if you want to make it in this world, you’ve got to pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” or other caveats, such as “everyone has a fair chance at doing well in school, getting a good job, and getting ahead.” Or, in the case of persons of color, citing skin color as a rationale for failure is only an excuse. According to Miljs and Usmani’s model, these and other similar perceptions behind the beliefs imply erroneously what dozens of sociologists have concluded in their research, that we live in a stratified society where social worlds have established networks of institutions patterned by class and race. One of the central theses of this model shows that as members of their social worlds, individuals in segregated networks are led to believe that inequality plays a minor role, and in fact, believe that success in life is overwhelmingly and largely attributed to individual talent and effort. According to the author’s statistical analyses, by virtue of their segregated network membership, people overestimate the value of talent and effort in achieving success while underestimating the following, they: underestimate the extent of economic inequality between racial and ethnic groups; underestimate the extent of the importance of social class and race in becoming successful; underestimate the extent of the importance of race-based discrimination on a historical basis; and on how inherited racial factors have disadvantaged people of color.

In addressing the basis for such undervaluing of economic inequality and belittling the importance of social class and race, the authors point to distorted perceptions behind these beliefs, which lead to inaccurate inferences. Members of segregated networks base their perceptions about race and class differences on a reality for which they lack the ability to correctly understand beyond what they experience. When focused on the formative institutions, which the authors have described as neighborhoods, schools, and market, referring to wage earnings, the computer model follows an undisturbed pathway that clearly demonstrates how segregation negatively affects how individuals perceive the extent of inequality. Essentially, segregation limits the kind and variety of persons that make up the social world networks, thus shaping the formation of distorted perceptions. In their model simulations, the authors found that the rich have minimal information about the lives of the poor, and vice versa. Individuals make inferences about inequality based on what they can and cannot see. An insulated environment that segregation yields, creates an invisible world that could otherwise inform the individuals of the causal factors inherent in inequality.

The authors are emphatic that empirical research of the last several decades underscores that segregation in our country is extremely high and growing. The segregated environments include neighborhoods, schools, and wage earnings, or simply, the life course. Gary Orfield, a prolific researcher specializing in school segregation, quotes in his book the following:

“Racial inequality, racial discrimination, racial segregation, and racial stereotypes are basic structures of our society, though many Americans do not see them or even accept their existence.” (46) **

The simulation model created by Miljs and Usmani not only confirms generational research but provides a broader view of how inequality spans and develops in breadth and depth throughout the lifetimes of families of color. The author’s principal message embedded in the article centers on a credible yet alarming message: their predictions signal a crisis of widespread proportion on how debilitating segregation can affect our democratic society.

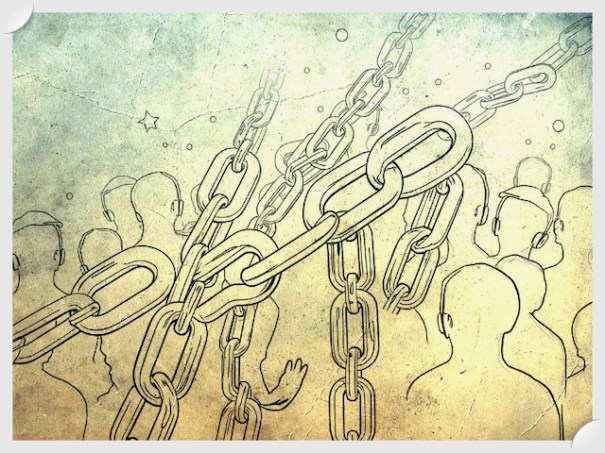

What researchers suggest is that segregation (inequality) is a self-perpetuating process. A stratified society such as ours produces segregated worlds and filters out the possibilities for individuals to become cognizant of the multidimensional effects of inequality in society. In an educational context, the students of color are more likely to experience prejudicial conditions and less likely to receive the needed support for academic success. It’s an unbroken chain as described by Hermann Hesse: … “an eternal chain, linked together by cause and effect.” Contrary to tacit assumptions, students of color systematically face unfair chances, and their racial or ethnic identity is often a reason for discrimination.

Miljs and Usmani’s simulated model is a powerful tool that serves to inform and establish relevant logical conclusions. It provides elaborate explanations on how segregation ruins descriptive and causal inferences, and how this impacts decision and policymaking with dire consequences. When high-stakes decisions are made by members of social worlds whose inferences about extent and nature of inequality are deformed (another term they use to describe distorted perceptions), their level of ability is impeded. How can our society place trust on decision-makers in charge of directing or managing vital tasks and operations when their views or ideological beliefs are false or distorted?

*Miljs, J., & Usmani, A. (2024). “How Segregation Ruins Inference: A Sociological Simulation of the Inequality Equilibrium.” Social Forces, 103, 43-65.

**Orfield, G. (2022). The walls around opportunity: The failure of colorblind policy for higher education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.